Before Jack Nicholson became a caricature of himself as the irrepressible bachelor-- grouchy, creepy, unserious, baffled, flippant-- he had a dazzling run deconstructing the modern everyman into a moral situationist. This was the early 1970s, the age of Vietnam and Watergate, when the template for role models had been tweaked by war and social upheaval. No longer was it clear what constituted the ideals of a hero-- hell, it was hard enough to say what made a man a man. Thus Hollywood, in an era of permissive genius, played the dialectical game with the society at large, attempting to answer the unanswerable, and speaking for the cause of elusive heroism, among many great actors of that time, was Mr. Nicholson.

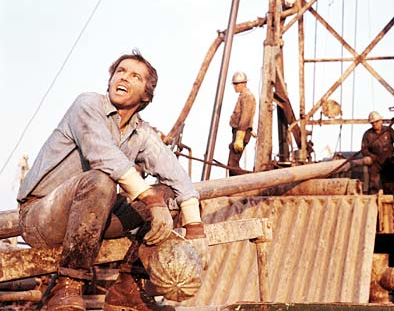

Before Jack Nicholson became a caricature of himself as the irrepressible bachelor-- grouchy, creepy, unserious, baffled, flippant-- he had a dazzling run deconstructing the modern everyman into a moral situationist. This was the early 1970s, the age of Vietnam and Watergate, when the template for role models had been tweaked by war and social upheaval. No longer was it clear what constituted the ideals of a hero-- hell, it was hard enough to say what made a man a man. Thus Hollywood, in an era of permissive genius, played the dialectical game with the society at large, attempting to answer the unanswerable, and speaking for the cause of elusive heroism, among many great actors of that time, was Mr. Nicholson.The character Nicholson plays in Five Easy Pieces, Bobby Eroica Dupea, is not easy to love. Bobby is a blue collar oil rig worker who drinks beer, goes bowling, and screws around on his needy girl, Rayette (a bizarre, yet likable performance by Easy Rider muse Karen Black), basically leading the kind of life today's Brooklyn hipsters stylize in pretense. Bobby's not faking it, of course; he just doesn't seem to know what else to do with his life and has accepted that work is something that funds the good times, which for Bobby have a generally masculine, if not anti-intellectual flavor. To the "carpe diem" type, it does seem a meaningless life, measured in sexual encounters and poker winnings. But as we observe the pleasure principle failing him, we discover that his appetites stem from a reaction to the sterile background from which he sprang.

Essentially, this is a story about family and like all the best stories that deal with the uncomfortable intimacy related to blood relations, Bobby doesn't necessarily get along very well with his kin. Interestingly, it is a clan of musical geniuses, but whose interest and virtuosity lie in classical persuasions, particularly piano greats like Chopin and Bach, indicating their personalities to be anachronistic and eccentric. Bobby's sister, though well-intentioned and kindly, is the spinster type. Bobby's brother--oafish, arrogant, clever-- has embraced the lifestyle as enthusiastically as Bobby has brazenly abandoned it. There is no mother in the picture but the family patriarch has had a stroke and though it's implied Bobby's father never quite forgave his son for walking away from a promising career in music, the prodigal son has come home.

The Dupea family live on a vast and beautiful estate on an idyllic island off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. It's an isolated place, funded by old WASP money one supposes, and immune to the cataclysmic forces destabilizing the 1960s individual. In such a place rock and roll simply does not exist, and neither does the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, or the uncertainty of the times. In such an environment there is no counterculture, only culture. Bobby, alone in the family, has put Dr. Pangloss's utopian theory to the test and besides the ephemeral joys of beer, gambling and sex, his wanderings have left him a slightly ruined man. What makes the character so interesting is that he is neither here nor there, a classic outsider, a classless American, who knows too much of either world to fit in properly and to like it. Neither social context works for him, leaving him essentially homeless, alone, and drifting.

And that's precisely why I find Five Easy Pieces to be one of the great archetypal 1960s films although in truth it's one part sex, zero parts drugs and rock and roll. But the 1960s were more than just Andy Warhol and Tim Leary. There was a whole generation of Americans that had nothing to do with Woodstock or Shamanism that found themselves at the end of a postwar boom, divorced, jobless, possibly derelict and if they didn't go for pot or long hair, probably lonely and alienated to boot. Bobby is not some stupid trust fund kid getting off his rocker. He is a strong personality who has found nothing to recommend any system. Too smart for his own good, he lashes out against pretentiousness and ignorance equally, often getting into physical scraps that leave him humbled. He just doesn't seem to have any good fight in him; or perhaps he just doesn't know what he's fighting for.

Bobby Dupea has no great loves or hates; if there is no American Dream, conversely there is no American nightmare. There's just the day-to-day attrition of trying to make an unbearable life bearable. That's where the beer and women come in--they're palliatives, not salvation, which to some temperaments will always remain suspect, and therefore disposable. He loses the one girl who really captivates him (his brother's girlfriend, played by the lovely and mostly forgotten Susan Anspach). She breaks things off because for a woman of expressed passionate views, Bobby's indifference is incomprehensible; there is no real future with him. She believes he is insensitive to beauty in life, but that simply isn't true. The difference between them is that sensitivity has destroyed him. While she loses herself in music, he has lost himself in the world.

In the film's famous monologue, Bobby explains to his ailing father, now mute but perhaps alert yet, "Most of what I do doesn't add up to a way of life that you'd approve of. I move around a lot, not because I'm looking for anything really but because I'm getting away from things that get bad if I stay..." It's a sentiment that Bobby lives by to the very end, resulting in a contentious ending that some viewers find quite objectionable. But it's an honest telling and it suggests so much about the uncertainty of that time.

It's not every character that needs to learn right from wrong. Sometimes, they're one of the same thing. And that's that.

One of my favorite all-time flicks. You're right about Nicholson having a bunch in a row during this era. You do something like that and you can play your Grumpy Old Man (wasn't he a stand-in for Mathau?) until you die (which in his case may be from a flying Ron Artest elbow on the Lakers' sideline). Your choice of films / books to review are are both piquant and refreshing. Leave it to the genius of Lotman to remind us all that we have much gold to (re)mine from the coffers before embarking upon another remake of a remake that was a B- movie in the first place. Keep Rocking On, amigo.

ReplyDelete