In the first few paragraphs of John Williams' novel, Stoner, we learn that the title character was born to rural farmers, taught English literature at a University and died rather quietly at age 64. By putting all of his cards on the table early Williams leads us to understand that this is not a dramatic story. Drama, however, is inessential if a character is drawn well enough. In such circumstances it doesn't hurt either if a modest life is explained in luminous prose. Williams succeeds on both counts and perhaps his sympathetic portrait is as good as it is because the omniscient voice is marked by its precision and economy. Williams may have published Stoner in 1965 but the novel has the serenity of late Victorian storytelling rather than the breezy tongue-in-cheek style of so many of his contemporaries.

In the first few paragraphs of John Williams' novel, Stoner, we learn that the title character was born to rural farmers, taught English literature at a University and died rather quietly at age 64. By putting all of his cards on the table early Williams leads us to understand that this is not a dramatic story. Drama, however, is inessential if a character is drawn well enough. In such circumstances it doesn't hurt either if a modest life is explained in luminous prose. Williams succeeds on both counts and perhaps his sympathetic portrait is as good as it is because the omniscient voice is marked by its precision and economy. Williams may have published Stoner in 1965 but the novel has the serenity of late Victorian storytelling rather than the breezy tongue-in-cheek style of so many of his contemporaries.Thursday, September 23, 2010

The Life and Times of a Stoner

In the first few paragraphs of John Williams' novel, Stoner, we learn that the title character was born to rural farmers, taught English literature at a University and died rather quietly at age 64. By putting all of his cards on the table early Williams leads us to understand that this is not a dramatic story. Drama, however, is inessential if a character is drawn well enough. In such circumstances it doesn't hurt either if a modest life is explained in luminous prose. Williams succeeds on both counts and perhaps his sympathetic portrait is as good as it is because the omniscient voice is marked by its precision and economy. Williams may have published Stoner in 1965 but the novel has the serenity of late Victorian storytelling rather than the breezy tongue-in-cheek style of so many of his contemporaries.

In the first few paragraphs of John Williams' novel, Stoner, we learn that the title character was born to rural farmers, taught English literature at a University and died rather quietly at age 64. By putting all of his cards on the table early Williams leads us to understand that this is not a dramatic story. Drama, however, is inessential if a character is drawn well enough. In such circumstances it doesn't hurt either if a modest life is explained in luminous prose. Williams succeeds on both counts and perhaps his sympathetic portrait is as good as it is because the omniscient voice is marked by its precision and economy. Williams may have published Stoner in 1965 but the novel has the serenity of late Victorian storytelling rather than the breezy tongue-in-cheek style of so many of his contemporaries.My Fated Disappointment with War and Peace, Briefly

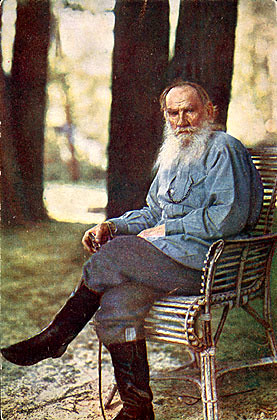

When people found out I was reading War and Peace this summer the most common question posed was, “Is it worth it?” To which I generally shrugged, sighed and said, “Yes and no.” For those who love literature and are interested in the evolution and idea of the novel, then it probably should be read. But for most of us, with all the options of books, not to mention various entertainments and outdoor diversions available, the answer leans towards No, that it is not worth it and that life is too short to read War and Peace. You can lead a wonderful life without ever knowing the Rostovs or the Bolkonskys or even its pontificating author.

When people found out I was reading War and Peace this summer the most common question posed was, “Is it worth it?” To which I generally shrugged, sighed and said, “Yes and no.” For those who love literature and are interested in the evolution and idea of the novel, then it probably should be read. But for most of us, with all the options of books, not to mention various entertainments and outdoor diversions available, the answer leans towards No, that it is not worth it and that life is too short to read War and Peace. You can lead a wonderful life without ever knowing the Rostovs or the Bolkonskys or even its pontificating author.This is not to say that I feel War and Peace is a bad book per se. Tolstoy does some marvelous work dramatizing one of the most cataclysmic events in Russian history. (Who will dramatize the Russian Revolution? It seems incredible that no Russian novelist has tackled that event and transformed it into a literary epic.) Tolstoy demonstrates a thorough capacity for detail, describing the nuances of aristocratic manners and the gruff speech of common foot soldiers with persuasive savoir-faire. His characters are lively and unique and undergo profound changes, grappling with responsibilities of war and career, marriage, finances, births, and death-- in other words, life in all its glory and banality. As some critics have suggested, should the earth write a novel, it might sound like Tolstoy.

But the Earth is not perfect and neither is Tolstoy’s book for that matter. We can generally gauge the quality of a novel using three primary benchmarks: the story, the characters and the style. War and Peace suffers from many digressions into the lives of periphery characters but remains compelling due to its dramatic historical nature. The main characters, as I mentioned, are mostly sympathetic, their humanity drawn out beautifully. It’s difficult to discuss style since War and Peace is a translation (I had the Anthony Briggs edition) so while we cannot judge Tolstoy by his prose, we can nevertheless opine on his structuring of the novel and the general pool of language he has chosen to tell that story. It is here that Tolstoy astonishes me with his narrative miscalculations. The problem is the author inserting himself into the story to make declarative points that relate to his celebration of a divine force. The unfortunate consequence on the reader is having to bear the lecturing of a writer guilty of a god complex. Little is left for us to interpret on his or her own. Everything must be explained according to the way Tolstoy intended it. He violates the cardinal rule of storytelling: show, don’t tell.

In doing so, Tolstoy comes off as an insufferable dinner companion. He never hesitates to interrupt the narrative with long-winded discussions regarding the scientific basis for understanding history (an irritating device that has no place in a novel! None!) but literature, though an aesthetic branch of the arts, is understood by rules established between authors and their audience. Of course these rules are malleable (art being more lenient than science) but to disregard them is done at the writer’s peril.

As everyone knows, whether consciously or intrinsically, good storytelling makes for an irresistible yarn: the writer instills in the reader the need to know what happens. Napoleon’s invasion of Russia was an incredible event, changing the course of history. Historical narrative is drawn out in both micro and macro formats-- the lives of individual characters contrasted with the nation’s larger struggle. I found Tolstoy’s telling at the micro level engrossing. For example, on the eve of the French entering Moscow, during the collapse of public order Count Rostopchin’s justification for throwing a criminal (traitor) into the mad violence of a crowd is apropos of Tolstoy’s insight into human character, in this case, a politician’s:

“Since time began and men started killing each other, no man has ever committed such a crime against one of his fellows without comforting himself with the same idea. This idea is the ‘public good…’” (Vol. III, Part III, Ch. 25)

Could a historical novel involving George W. Bush’s faith in the Iraq War be written any different? In a thoughtful meditation on the wastefulness of armed conflict, Tolstoy, speaking through Andrei Bolkonsky in a midnight oil heart-to-heart with Pierre the night before the Battle of Borodino would destroy the young prince, suggests:

“If we didn’t have all this business of magnanimity in warfare, we would only ever go to war when there was something worth facing certain death for, as there is now.” (Vol. III, Part II, Ch. 25).

Here is Tolstoy at his very best, pensive and theoretical, but, importantly, expressing himself through his characters. His narrative problems come when he enters the scene, for example, carrying on about troop movements, particularly the fate of the French army making the catastrophic blunder of retreating on the Smolensk road, which had seen the land around it plundered and destroyed and so would not provide the needs for Napoleon’s massive army. Tolstoy wastes our time with endless dissections of this blunder, reveling in it, repeating it, and in the end, boring us with such eye-glazing assertions and unnecessary sarcasm:

“This was done by Napoleon, the man of genius. And yet to say that Napoleon destroyed his own army because he wanted to, or because he was a very stupid man, would be just as wrong as claiming that Napoleon got his troops to Moscow because he wanted to, and because he was a clever man and a great genius. In both cases his individual contribution, no stronger than the individual contribution of every common soldier, happened to coincide with the laws by which the event was being determined.” (Vol. IV, Part II, Ch. 8)

This paragraph propels two important theories of Tolstoy’s. First, that historians put too much weight on single individuals (personalities) guiding history-- in doing so, they fail to cite the billions of contingencies that determine world events (which are God’s doing). Secondly, it’s another opportunity for Tolstoy to criticize Napoleon. Sometimes it feels he wrote the book for the purpose of excoriating Napoleon to a general reading public. Throughout the novel but especially in the epilogue, Tolstoy goes out of his way to downplay his achievements, arguing that Napoleon was simply an egotistical, arrogant opportunist at the right place and the right time.

This is the book’s greatest failure: not his antipathy for Napoleon-- Tolstoy is entitled to his likes and dislikes-- but that his arguments overwhelm the storytelling in pompous cant. According to biographers, Tolstoy turned to literature as a young writer after being disenchanted with history. In his second epilogue, he spends more than 40 pages (in technical, colorless, dull language) disparaging the work of historians on the premise that they are unable to differentiate the actions on mankind, whether it be free will or motivations built from necessity. What he seems to suggest, dramatically in Napoleon’s retreat and the marriages of Pierre and Natasha and Nikolay and Marie is that they were predestined by a supernatural force. It was all meant to be:

“And just as the indefinable essence of the force that moves the heavenly bodies, the indefinable essence that drives heat, electricity, chemical affinity or the life force, forms the content of astronomy, physics, chemistry, botany, zoology and so on, the essence of the force of free will forms the subject matter of history.” (Epilogue, Part II, Ch. 10).

A decade before Tolstoy composed his thoughts on this subject, Charles Darwin had published his Origin of Species, whose arguments of evolution refute Biblical infallibility. Probably, its evidence threatened Tolstoy’s vision of the world. Obliquely referencing Darwin’s thesis, he argues that,

“in the frog, the rabbit and the monkey we can observe nothing but muscular and nervous activity, whereas in man we have muscular and nervous activity plus consciousness.” (Epilogue, Part II, Ch. 8)

But this confuses me. What is the importance of consciousness if everything is divinely predetermined? Is it so we can recognize and celebrate God? And why are we even getting into this? On abstract terms rather than through the prism of the characters’ actions or dreams? Imagine John Steinbeck ending The Grapes of Wrath not with that lovely and tragic scene of the Joads’ pregnant daughter sharing her breast milk with an emaciated stranger but the novelist spending thirty pages examining the causal effects of the Great Depression and the merits of the New Deal. I’d love to read Steinbeck’s views on politics, but preferably in a chapbook or a magazine interview format.

In the epilogue Tolstoy ignores the Rostovs and Bolkonskys, only bothering to mention Napoleon (for one last drubbing) in his final descent into didacticism. Beyond whether or not Tolstoy is persuasive in his argument is besides the point. The best storytelling weaves philosophy into its narrative without resorting to pedantic posturing. I found Tolstoy’s voice irritating, his arguments confusing, his language obfuscating. Not to mention hypocritical. After lambasting historians for telling us how to interpret events, he goes and instructs us himself. The nerve of great minds!

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful

“We’re on the cutting edge of reality itself. Right where it turns into a dream.”

It’s hard to believe that there has been no great Vietnam War novel. The war has been better served by memoirs (Ron Kovics’ Born on the 4th of July and Neil Sheehan’s Bright Shining Lie) and especially cinema (Apocalypse Now and Coming Home, among others). Perhaps the best story about the conflict may be Graham Greene’s The Quiet American but that was written by a Brit in 1955, before the conflict became a national security issue making front page headlines. Back then it was but one of the many stories of decolonization rapidly transforming geopolitics in Asia and Africa in the 1950s. At the time of Greene’s novel it wasn’t quite yet the war it became, an ideological civil war between North and South lasting more than 15 years. The great World Wars were comparatively brief. Is it for this reason that Vietnam defies the ambition of writers in recasting the war in a poetic narrative? Is it just too damn big, ugly, and morally wrong? Where would you even begin?

It shouldn’t be so. After all, moral dilemmas make for some of the best reading. Into this discussion rides Denis Johnson and his Vietnam novel, Tree of Smoke. At first glance, it wouldn’t seem that Johnson, famous for his poetic tales of dropouts and ex-cons in books like Angel and Jesus Son would be the kind of guy to give the Vietnam War its just due. But this isn’t quite about politics or platoons as it is about personalities, dreams, and God. The hall-of-mirrors confusion of such a setting is perfect for a writer like Johnson, a writer that revels in tricky storytelling and moral ambiguity. Rather than going there, he prefers tumbling down the slippery slope of Manichean worldviews. When everyone is just trying to stay alive in a place as brutal as ’Nam, who are the good guys anyway? Literature being a Western art form, in a cross-cultural conflict we tend to write from our side of things. Among various detailed atrocities, to save us from a supposed Communism menace, our government employed seven-ton super bombs against North Vietnam, capable of decimating 8000 square meters. Into this inferno we also dropped Spiders, small grenades with near-invisible antennas that were detonated upon touch. They were designed to kill survivors helping the wounded or putting out fires. And for what purpose in the end? The defeat of an exaggerated Communist means. No, the end never justified the means. While Johnson describes little of the fighting itself (besides the Tet Offensive), at times he captures the situation’s moral ambivalence perfectly:

“They threw hand grenades through doorways and blew the arms and legs off ignorant farmers, they rescued puppies from starvation and smuggled them home to Mississippi in their shirts, they burned down whole villages and raped young girls, they stole medicines by the jeepload to save the lives of orphans.”

The closest we come to a concept of a hero (in the Greek sense: military honors, hubris, appetites, tragic trajectory) is an alcoholic raconteur, Colonel Sands. Running a renegade CIA outfit with his nephew and a few aids, he understands that the Vietnamese goal of self-determination may be too powerful for the U.S. to win the war no matter how many bombs are dropped. However, he believes in a certain hearts & minds strategy:

“This land under our feet is where the Vietcong locate their national heart. This land is their myth. We penetrate this land, we penetrate their heart, their myth, their soul. That’s real infiltration. And that’s our mission: penetrating the myth of the land.”

Ironically (or perhaps not very much so), the colonel’s base is above Cu Chi, the famous tunnel network from which the Vietcong conducted guerilla warfare. The Colonel is a true Cold War Warrior, a legend of his own time, with nearly three decades experience in Asia battling “evil.” In Vietnam his status or relationship to the Top Brass is enigmatic and it seems his scheming is likely outside of the military hierarchy or jurisdiction. Even his relationship to leadership in the CIA seems sketchy. Like an artist or perhaps a conman, he is looking beyond military strength to defeat the enemy. In the colonel’s world, mindfucking can be just as powerful as strategic bombing, as this memo conveys:

Ironically (or perhaps not very much so), the colonel’s base is above Cu Chi, the famous tunnel network from which the Vietcong conducted guerilla warfare. The Colonel is a true Cold War Warrior, a legend of his own time, with nearly three decades experience in Asia battling “evil.” In Vietnam his status or relationship to the Top Brass is enigmatic and it seems his scheming is likely outside of the military hierarchy or jurisdiction. Even his relationship to leadership in the CIA seems sketchy. Like an artist or perhaps a conman, he is looking beyond military strength to defeat the enemy. In the colonel’s world, mindfucking can be just as powerful as strategic bombing, as this memo conveys:

“…Consider the possibility that a coterie or insulated group might elect to create fictions independent of the leadership’s intuition of its own needs. And might serve these fictions to the enemy in order to influence choices.”

The Colonel’s number one point man in carrying through his plans with a double agent is his nephew, Skip. Skip likes languages and has a mustache. “Always a sucker for sardonic, myopic, intellectual women,” he enjoys a fling with Kathy, a missionary in the Philippines, who also relocates to Vietnam to help orphans and who writes Skip digressive letters that make him uncomfortable. Kathy “wasn’t, herself, beautiful. Her moments were beautiful.” But Skip is mostly alone in a countryside villa that once belonged to a French colonial doctor who went mad in isolation and whose obsession with tunnels was his mortal ruin. Skip, bored with a pre-Internet burden of cataloging everybody or everything associated with the war up to that point spends hours translating the deceased doctor’s diary entries, including the following:

“Is the mind a labyrinth through which the consciousness gropes its way or is the mind the boundless void in which certain limited thoughts rise up and disappear?”

It feels like Johnson’s own consciousness is in on this labyrinth. The novel feels piecemeal at times, following satellite characters to dead ends. The book often reads like a screenplay or a poem, shifting between bizarre conversations and weird prose. Johnson is capable of lovely, nuanced language and it is for the writing more than anything else that one reads Denis Johnson. However, sometimes you just don’t know what to make of him. Getting carried away with the kooky, psychedelic nature of the war, Johnson occasionally fails to articulately establish setting:

“He crouched by the window and listened shuddering to the sound of ripped high-voltage wires out there stroking the darkness, humming closer and farther, feeling along the darkness after fear. The voltage sucked along the shaft of fear toward any heart emanating it and burned the soul right inside it. That was the True Death. Thereafter nobody lived in that heart, nobody saw out of those eyes. The stench of such burning floated in and out of the room all night.”

But I’m nitpicking. If the story and its scenarios are confusing, it’s only mirroring the war. The novel’s titular Tree of Smoke has Old Testament connotations as well as, of course, an atomic reference to widespread devastation. It’s also about something that has a shape but no actual being, much like what happened to our soldiers who fought there. War is brutal enough when it’s waged with something at stake. But when we have to invent principles, the line between tragedy and farce blurs, just as our notion of heroism. In such battlefields, many one-eyed kings are crowned:

“You’re sad about the kids, sad about the animals, you don’t do the women, you don’t kill the animals, but after that you realize this is a war zone and everybody here lives in it. You don’t care whether these people live or die tomorrow, you don’t care whether you yourself live or die tomorrow, you kick the children aside, you do the women, you shoot the animals.”