Robert Altman’s film, “Nashville” holds that mirror up and never drops it. This is a movie very much about time and place, which means it is about crossroads. Nashville, the city, is located on the Cumberland River in northeast Tennessee, an historic middle point, halving the country between North and South and until the railroads reached California, lay betwixt the settled Eastern seaboard and the Mississippi frontier (it was a “border” state that fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War).

Made at a troubled junction in time (post Vietnam and Watergate), the film is curiously tied together by the pervasive presence of a roving electioneering van. It plays the prerecorded voice of Hal Phillip Walker, a fictional candidate of the Replacement Party railing against the system in populist rhetoric, articulating the era’s disenchantment with taxes, cronyism, the job market. This demagogue’s blabbering matter-of-fact rationale goes mostly unnoticed by the characters of “Nashville,” many of whom are too self-absorbed to consider politics as something worth their commitment. The 1960s are over and anyways this isn't California, this is Nashville. (Jeff Goldblum's weird motorcycle man riding around in his Haight Ashbury duds on a low riding 3-wheeler is just about the only hippie and no one takes him seriously-- the Easy Rider generation at this point was more of a caricature than a threat to the lifestyle of good o' Southern boys, who have grown their own hair long anyways.) The characters of Nashville are not interested in what might make America a better country and they certainly wouldn't want to think about logistics: these are Me Generation people with personal agendas. In their various pursuits of power and satisfaction they are sexually promiscuous, high-strung, opportunistic, and yet, often, unfailingly idealistic about one’s possible place in the world. Thus, the American Dream, for all its nasty surprises and disregarded caveats, is very much alive here.

Made with the signature Altman flair, “Nashville” has no genuine hero (“heroism:” a troubling concept in this time anyways) but follows two dozen characters in the city of Nashville during a spirited five days of music, sex, and politics. The film is populated by country music stars, political kingmakers, aspiring singers, and this being about the music industry, groupies. These are imperfect men and women, but this isn’t a bad thing, necessarily—it’s honest and most of the time men and women are doing whatever they can to get ahead. This, the system may not condone but it has always looked the other way. Too rarely does a filmmaker suggest with his characters that the audience should watch their judgment, as in, “What about it? You think you’re better?”

To make it anywhere in America, talent may not be as crucial as ambition. You might even say it is more important to be than to do as in, “I’m a singer” rather than, “I sing.” Identity politics is the unconscious game as it conveys our usefulness to others. There are plenty of “celebrities” in Nashville, to whom an audience projects its sense of destiny. In Nashville this means we want to flatter them, fuck them and even murder them. Power is one of the most slippery slopes. The made-it country music stars understand that fortune fluctuates and that today’s hit is tomorrow’s oldie. They may sing sentimentally about love, but there’s not much of it to go around. Sex is about as far as the promise goes…

Typical of Altman, with so many characters to pick through, plot, at least in a classic conflict/resolution structure we’ve been weaned on, fails to materialize. There are performances at the Opry, political fundraisers, major traffic accidents, bedroom scenes. His touch is subtle. What seems unrelated, isolated, or random may be superfluous if plot is one’s goal but Altman is exploring ideas. As a result, the performances feel extremely natural, so that the experience becomes as voyeuristic as it is thoughtful. In spite of it being about the capricious and malleable quality of power, the theme never slips into darkness, for the film is too clever and humorous to make us feel awful about things. In other words, there is no “good” or “bad” in the film, there’s just humanism, which may be about doing the wrong thing at the wrong time, but surviving somehow. You may not identify with these kinds of characters but you can certainly sympathize with them.

As good as the acting is, “Nashville” may be most significant for its songs. This is the last great era of country music before Nashville as a sound became glossy, sterile, and trite. These are songs embodying the last years in which country music sounded ‘country’ in the way that it was “of the people, by the people, for the people.” Today, one rarely hears the human touch on a country music record. It sounds like music by committee, programmed for suburban Sony stereo systems.

In the opening credits Henry Gibson is recording an amusing patriotic ditty, drawling, “We must be doing something right to last 200 years.” Keith Carradine sings, “I’m Easy” to an audience that includes multiple lovers, each of whom fancy the song is a personal love letter. Ronnie Blakley plays Barbara Jean, a diva inspired by Loretta Lynn, a convincing cult of personality portrayed as a troubled angel, for whom fame is fated to be tragic.

And then there is Barbara Harris, who plays Winifred, a down-on-her-luck wannabe who is fleeing her husband. She has holes in her tights, lugs a big bag of laundry, poaches sandwiches at catering events. Moving like an animal, twitching, instinctive, looking by all conventional wisdom, a crazy. Yet, in the end, it is she who gets her big break on a stage before thousands in the most dramatic fashion possible. In a magnificent soprano backed by a black choir, she rehabilitates a traumatized audience, getting them to sing along with what might as well be a chain gang work song, whole-heartedly embracing lyrics that are upbeat, celebratory, earnest, yet completely absent of irony, “You might say I’m not free...It don’t worry me.”

And then there is Barbara Harris, who plays Winifred, a down-on-her-luck wannabe who is fleeing her husband. She has holes in her tights, lugs a big bag of laundry, poaches sandwiches at catering events. Moving like an animal, twitching, instinctive, looking by all conventional wisdom, a crazy. Yet, in the end, it is she who gets her big break on a stage before thousands in the most dramatic fashion possible. In a magnificent soprano backed by a black choir, she rehabilitates a traumatized audience, getting them to sing along with what might as well be a chain gang work song, whole-heartedly embracing lyrics that are upbeat, celebratory, earnest, yet completely absent of irony, “You might say I’m not free...It don’t worry me.”

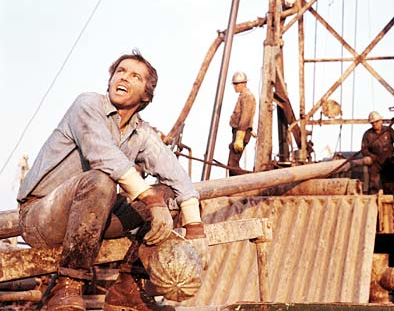

There, before a political rally masquerading as entertainment, the violence of American life strikes and when it does, it does not need to be explained. It just feels inevitable. Yet in the ashes of gun smoke, a star is born. The audience applauds its appreciation. The Stars and Stripes flutters gracefully in the wind. The American Dream lives for another day. This “dream” may seem stingy to most of us but when it does strike for an individual, it gushes, like a geyser in a Texas backyard.