The End of the Romanov Dynasty

In 1884, a lovely 12-year-old princess, Alix, daughter of Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt and granddaughter of the illustrious Queen Victoria, traveled to Russia for the occasion of her elder sister's wedding to the Grand Duke Serge, brother of Emperor Alexander III. It was at this relatively insignificant royal union that young Alix met young Nicholas, the Tsar's 16-year-old son. Nicholas fell hard for Alix and they were eventually married. She bore him four daughters and, finally, one son, Alexis, the heir to the throne. Alexis was a delicate child, bruising easily. He suffered from hemophilia, a condition in which blood fails to properly clot when wounded. Hemophilia is a genetic disease found in the female X chromosome and passed to male offspring. The elder women in Alix's family tree, including Queen Victoria, were carriers of the disease. Alexis was cared for by many doctors until the Royal Family--particularly the Tsarina--embraced the special healing powers of the wandering mystic, Rasputin. When the First World War broke in 1914, the Tsar left to lead the Russian armies on the Eastern Front. His wife, plotting with Rasputin, disputed with the Duma and the people. Rasputin, a notorious alcoholic and womanizer, abused his influence over the Tsarina to a breaking point. One day in March a bread riot turned political. The Russian Revolution had begun. Within a very short time, the Royal Family was captured by Bolshevik forces and a few years later, executed en masse in the foothills of the Urals at Ekaterinberg, in July 1918, ending more than 300 years of the Romanov dynasty.

Thus, in other words, a rare genetic condition is hugely responsible for the Russian Revolution and the not-small repercussions, or so the author, Frederick Cartwright, suggests in his fascinating collection of conjecture called, straightforwardly, "Disease and History." In it the usual suspects are rounded up: the Black Plague, smallpox and the indigenous Americans, malaria and the inaccessibility of the African interior. But there are some interesting speculations, particularly when diagnosing the madness of certain monarchs, most especially Henry VIII and Ivan the Terrible, who began their reigns as firm, even heroic kings, but straying into bizarre if not catastrophic policy, were most likely victims of syphilis, insanity being one of its chief characteristics.

Disease, of course, is most often spread during the initial contact between foreign cultures. When a population lacks immunity, disease spreads very much like a wildfire does, leaping from person to person. If we go back to antiquity, it's very well known that it was in the post-Christ decades that Imperial Rome began its serious decline. Mainly, this is attributed to corruption and incompetence at administrative levels as well as a series of barbarian invasions. But what goes underreported is the scale of disease brought with Germans and Huns. Disease meant agricultural fields were abandoned, leading to famine. In a situation of scarce resources, war becomes inevitable (Cartwright, though he writes like a secular humanist, loves invoking the Four Horsemen to drive his point). It was in this period of massive death that Christianity found many converts. This was partly because of the generous afterlife promised to believers, but also because many of the miracles attributed to Jesus (especially by Luke) are those in which divine intervention equates to the healing of the sick. Many Christians became physicians but not very competent ones. Like the Greeks and Romans before them, they propitiated, but to various saints, rather than demigods. Should a person fail to heal properly, they figured there had been an error in the protocol or the wrong saint had been appeased. Working as faith healers rather than as empiricists they would control medicine's school of thought as such through the Dark Ages.

Street Scene, Black Death

Nearly a thousand years later, these charlatan doctors were bamboozled by the Black Plague. It's hard to contemplate the physical as well as the psychological impact this had on Europe. The Pope had to bless the River Rhone so that corpses dumped into its currents would have a proper Christian burial (what that did to the drinking water, down river, I do not doubt). Whole frigates lost their crews and these ghost ships drifted unmanned in The North and Mediterranean Seas. And then there were the flagellants, who saw the plague as divine punishment for man's sins so as to spare communities (and themselves) they would publicly whip themselves to appease a vengeful God.

Why Flagellate Without an Audience?

For the flagellants, their masochism wasn't worth a damn if they happened to encounter someone contagious. What made the plague of the 14th century so catastrophic was that it was pneumatic, meaning it was spread by cough, sneeze, drool, or sharing an ale. The Europeans failed to isolate the disease despite ingenious attempts (it is from the Black Death, we get the word "quarantine," as infected ships coming into port in Venice were isolated for forty days--

quaranti giorni). Cartwright has some interesting ideas regarding the consequences of The Black Death. For example, Jews in France and Switzerland were scapegoated and persecuted, instigating a voluntary relocation to Eastern Germany and Poland, thus connecting the plague to the Holocaust 600 years later. There was also the damage the plague did to the Church's reputation, which of course, appeared feckless in challenging the disease and saving its victims, doing much to expose its flaws as an institution. Many of the best parish priests died and were replaced with unscrupulous men. John Wyclif emerged in England, condemning these crooked priests for their sale of indulgences and other acts of avarice. Wyclif's ideas influenced John Huss of Bohemia, who in turn, turned on Martin Luther. Protestantism eventually led to the Puritan movement and their relocation to America (thus leading all the religious zealots to relocate to the New World).

Columbus's historic landing in the West Indies:

invisibly, bacteria are digging the moment most

One of the first major consequences of the Age of Discovery, epistemologically speaking, was the introduction of syphilis into Europe. It might have come with Columbus from the New World or it might have come via Portugal with Henry The Navigator, who was then opening up to the possibilities of the slave trade in Africa, but its symptoms in Europe are first recorded in the early 16th century. Famous for being venereal, initially it was passed through skin or oral contact. Syphilis was devastating to the layman, but here Cartwright is concerned with its effect on two monarchies. As mentioned earlier, one of the phases of the disease is a complete abandonment of common sense. Judging by his moniker it is not much a stretch to guess Ivan the Terrible went a little nuts. He is a well-known sadist who did not find piety irreconcilable to his bloodlust, to wit: "Ivan prayed with such fervor that his forehead was permanently bruised from his prostrations. These bouts of prayer were relieved by visits to the torture chamber, conveniently situated in the cellars."

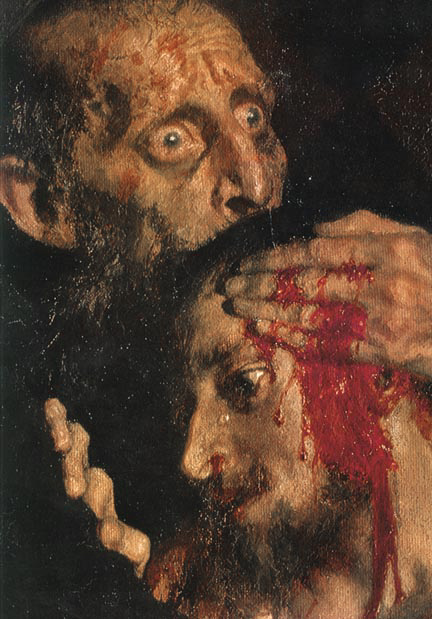

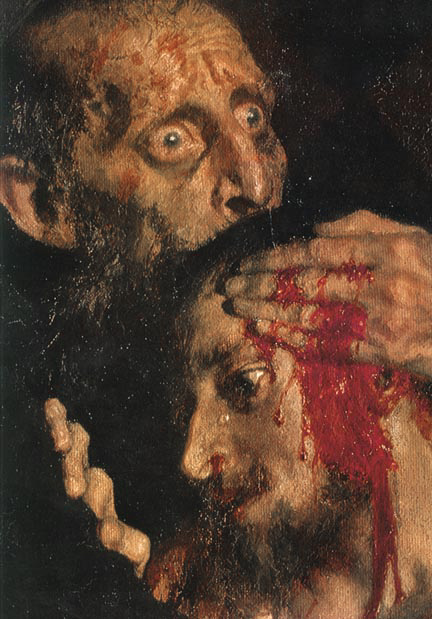

"What have I done?"

a depiction of Ivan having just murdered his son and heir

Of course, by suggesting the legendary Henry VIII was also a syphilitic, is a very great offense to a very great number of Anglophiles. But Cartwright makes some good points. Those familiar with Henry VIII know he suffered from gout, married six women, and famously broke with the Church (in better times he had been nicknamed 'Defender of the Faith' by Pope Leo X).

Cartwright, looking at the evidence, can only speculate but he believes it was syphilis that had prevented the Mighty Lion from producing a healthy male heir. There were numerous miscarriages among his wives and his surviving children suffered from some defects. Edward and Mary were physically and mentally unstable and Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen, may have waived marriage fearing her own sterility and the pressures she would have undergone to produce an heir (syphilis is congenital, passed from mother to child in the womb). Impotence is also a symptom and perhaps Henry had become fickle with his wives, abandoning them when they failed to arouse him. Anyways, we're just having fun here at Henry's expense, but could possibly the Church of England (and eventually then the English Civil War) have evolved from a lapse of judgment caused by an STD? Nothing is impossible...

Henry VIII with Jane Seymour and Prince Edward

Any discussion about disease must eventually lead to talk of a cure and one of man's most ingenious developments as an empiricist was his innovative discovery of the vaccination. Smallpox was a notoriously terrorizing disease, killing off large numbers during outbreaks. But it was learned that should a person survive a mild case, he or she would develop immunity. Thus it made sense that a person should have some exposure to smallpox rather than none at all. This idea of "inoculating" a person-- contaminating a healthy person with a disease-- goes back a millennia to Chinese medicine but was regarded as suspicious by the medical establishment for decades until some brave, innovative physicians were able to prove its effectiveness. Today smallpox no longer exists in the developed world and is very rare anywhere.

Map of Africa, 1773:

notice how little of the interior is catalogued

Similarly, it was centuries before the Europeans were able to successfully explore the African interior. Until the mid-19th century, it was believed that Europeans could not travel in Africa because of unique racial composition: "Medical opinion held that the white man could not perform manual labor in the African climate without falling sick. Thus the white man's function was to direct and to govern; only the Negro could carry out heavy work." The reason for the widespread sickness was, of course, malaria, which comes from the Italian meaning "bad air;" it was yet another error in understanding the roots of the disease. Not until scientists learned mosquitoes were responsible for the transmission of malaria were they able to isolate the disease. When they discovered mosquitoes are bred in dank water, swamps were drained and canals cleaned, thus reducing not only the chances of malaria but that of cholera as well. There is still no immunization from malaria, but it was discovered that quinine, an active alkaloid from cinchona bark (a tree located in Peru), kills the malarial parasite and is somewhat effective in prevention and treatment.

During the twentieth century, we have been so successful at understanding disease-- its causes, symptoms and treatment-- that we have seen our numbers grow exponentially. This problem of population is what Cartwright discusses in his conclusion and he forms an argument that our problems largely stem from man's instincts of self-interest as well as his ethnocentrism. He pleas to our humanity: "If man destroys himself, his destruction will most probably result from his obsessive emphasis upon the differences rather than the similarities between the races and nations. The primitive hates and fears are still with us, ready to break through the thin skins of civilization. Hate and fear cannot form a basis for the world-wide cooperation by which alone Man can save himself."

It's a wonderful sentiment but unfortunately outside the ingenious capacity of scientists. Economic markets and the governments that move "the invisible hand" are not concerned with management of resources, observance to the environment, and the well being of man. For the health care and pharmaceutical industries the bottom line is that a major disease outbreak requiring vaccinations, pills and treatment would be good for business. Until this reality is met with serious reform and a wholesale evolution of popular sentiment then we shall remain at the precipice.

Malarial victims, Africa

This, likely, will be the final verdict on man as a species; whether he is meant to endure or to be extinguished.